Change, like dynamite, comes in small packages

About Bayanda Mzoneli

Bayanda Mzoneli is a public servant. He writes in his personal capacity.

Last week I berated Dambi (aka Mazinyo) for liking a Facebook comment that had homophobic undertones. Dambi is a young female activists who serves in various structures of liberation movement, and appears to be destined for bigger responsibilities.

In berating her, I mentioned that as an activist she should attempt to bridge the gap between the values she feigns to espouse for political reasons, and the her actual values. Time will tell whether that message fell on deaf ears.

As an armchair revolutionary, I try to practice the values I feign to espouse, as far as possible. A venn diagram of the values and practice need not be two separate circles.

One of the least known facts is that Section 13 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa says, “No one may be subjected to slavery, servitude or forced labour.” For the purposes of this text, I am going to ascribe a meaning to “servitude” that includes chores conventionally expected of wives, girlfriends, and girl children.

Conventionally, it is expected that cooking, child minding, cleaning, washing and other household chores are performed by women. For some women in the past, and to some extent, in the present, the execution of these chores is seen as a rightful necessity, and something to be proud of.

A social construct that has been passed on for many generations can evolve into an innate attribute. It contains reinforcing factors, such as men who may be bad at cooking. As such, a wife would rather cook than eat boiled food, or risk poisoning from a poorly executed internet recipe.

All this is good and well. Many generations have survived off the servitude of women. It is likely that some outliers would take longer to adapt. But the reality is that the world is changing, and it ought to change.

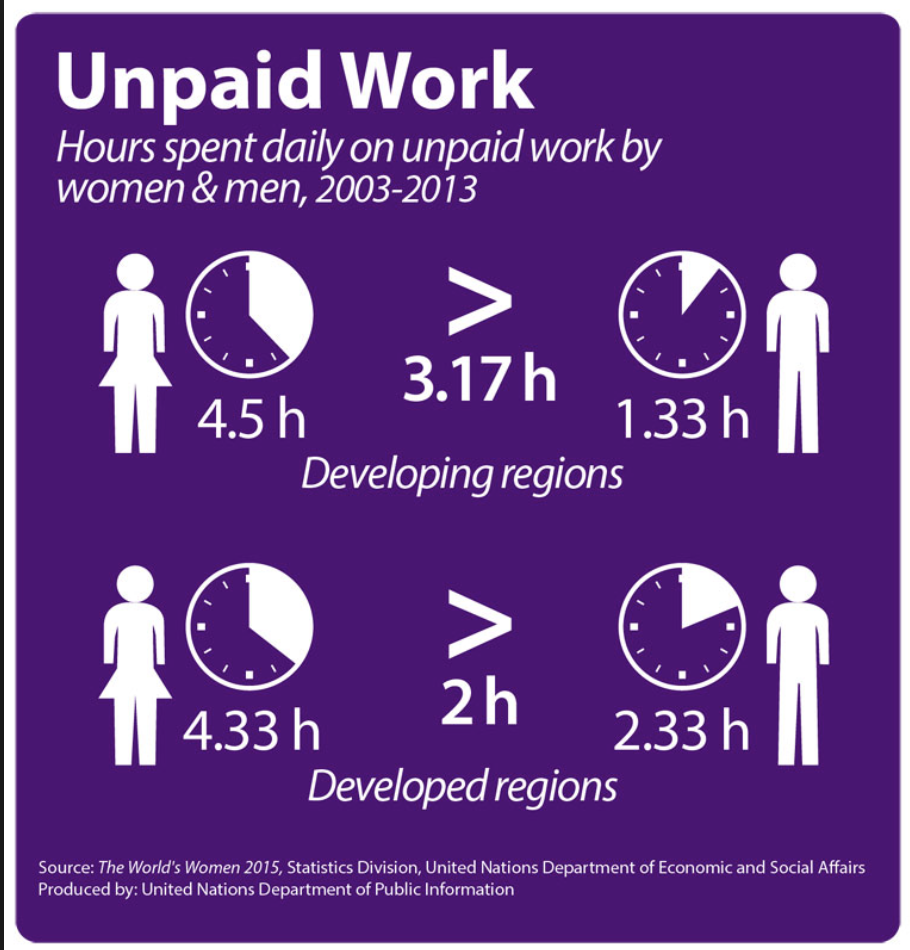

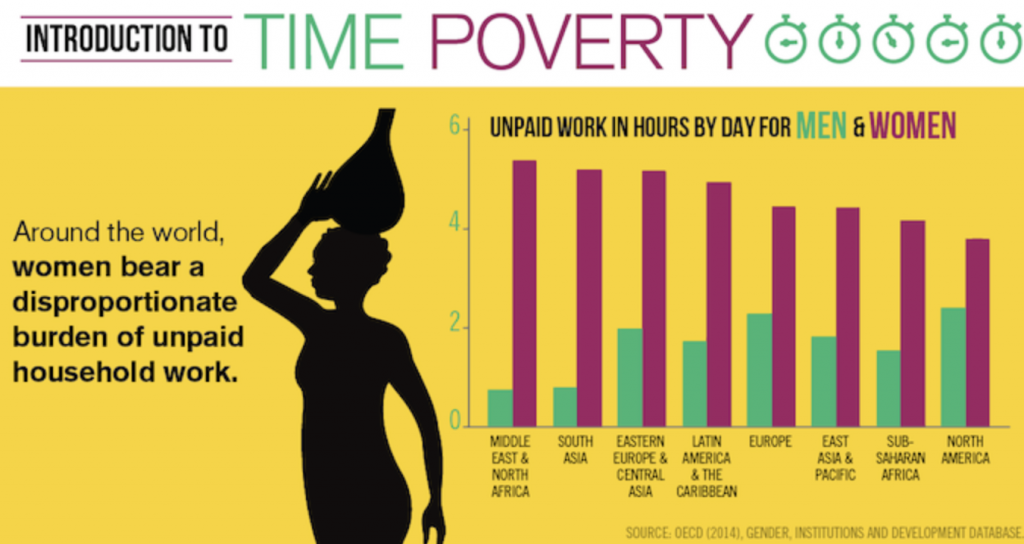

Various studies have began to ask difficult question about what is termed unpaid work. Studies suggest that in developing countries, such as South Africa, on average, women spend 4.5 hours per day on unpaid work, while men spend only 1.3 hours per day on unpaid work. See the graphs below from UN and OECD, you may google more.

There are some of us who see this situation as unavoidable, something we have to live with. But there are some of us, particularly men, who ought to be conscious of our privilege, and begin to reflect on what to do about it.

Ayanda (my daughter) is 12 years old. It is unlikely that gender equality would be achieved by the time she is an adult. But that is not a sufficient reason for me, as her father, to do nothing, within my means, to tilt the scales in favour of equality.

In an effort to tilt the scales, her and I entered into a bilateral agreement in 2018. The bilateral agreement says every time it is her turn to wash the dishes, she can ask me to do it in her stead, when I am around. In return she has to write a two page essay/story about anything. Although the agreement was signed in February 2018, she has only called on it 3 times, up to 13 March 2019. I am yet to consider why she is not calling on it more often.

Last week, we had to lay my late cousin brother to rest. Her daughter, my niece, as part of cutting costs, had suggested that her and her friend, plus other women from the extended family would do the chopping and cooking for the funeral.

In the Kingdom in the east, events of this nature are even called Umsebenzi (a Zulu word for work), though most men would probably translate it to mean Feast to avoid acknowledging their privilege. It is never acknowledged that it is UNPAID work.

To avoid getting all philosophical on my grieving niece, I told her that I have some discomfort with them doing the cooking, which I will explain to her some other time. But if that is what they had resolved, I would not stand in their way.

Fortunately, the caterer came back a day later offering a 30% discount from her original price. I was pleased that this would free my niece to mourn her father instead of spending the night chopping and the morning cooking.

Sadly, this week we lost our grandmother. We are attempting to have the funeral this weekend to avoid incurring the costs of criers. The discussion has come up again, with my cousin brother informing me that their wives, and our cousin sisters, will handle the catering, so we have to remove it in the costs on the spreadsheet.

I have agonised on whether to express my discomfort in the extended family WhatsApp group or let this slide. I settled on writing this blog, whose link I will post on the WhatsApp group. I do not know what would be ultimate decision on this, though I feel strongly that women in the family should be freed to mourn our gogo instead of being confined into kitchen chopping and cooking.

Subverting this convention in the family is not my original idea. It was started by my younger sister, Nontokozo. After she started working, whenever there would Umsebenzi at home, she would hire a helper and bring her home to chop and cook on her behalf. Her reasons may have been different but they fit to the point of this text. When she hosted us for Christmas last year, I was the one sweating in her kitchen while she chilled with a bottle of fermented grapes. I digress.

Obviously, nothing prevents converting the same unpaid work into paid work by remunerating the family members who execute the work by the amount equivalent to what would have been paid to the caterer, or even more, adding the family premium. The difference, however, is that that ought to be a choice they freely make, not servitude or forced labour, that is prohibited by the Constitution. In any case some of them may have no interest in becoming entrepreneurs in mass catering. It need not be imposed on them.

Privilige may suggest that the paying of lobola of 11 cows entitles men to a lifetime of servitude. It would even present as evidence that, on the wedding day, both families sang in unison, “Umakoti ungowethu, siyavuma, uzosiphekel’ asiwashele, siyavuma, sithi yelele yelele, siyavuma...” Nothing could be more nonsensical.

Of course, the chopping on the eve of Umsebenzi, is also an opportunity for women to catch on illuminating gossip. Brides gain insights about their husbands from their sisters-in-law and aunts-in-law that may not ordinarily be readily shared. But chopping is not a requirement for gossip to happen.

Just like the priviliged men often reminisce about who slaughtered the beast at which Umsebenzi, some women may derive fulfilment and contentment at that they cooked the best food to send off their loved one. It is may be recounted with a sense of pride that some barely slept since they chopped until early hours of the morning.

Perhaps in the past, conditions existed that necessitated and enabled such disproportionate abuse of women to prevail. We have no reason to let this continue.

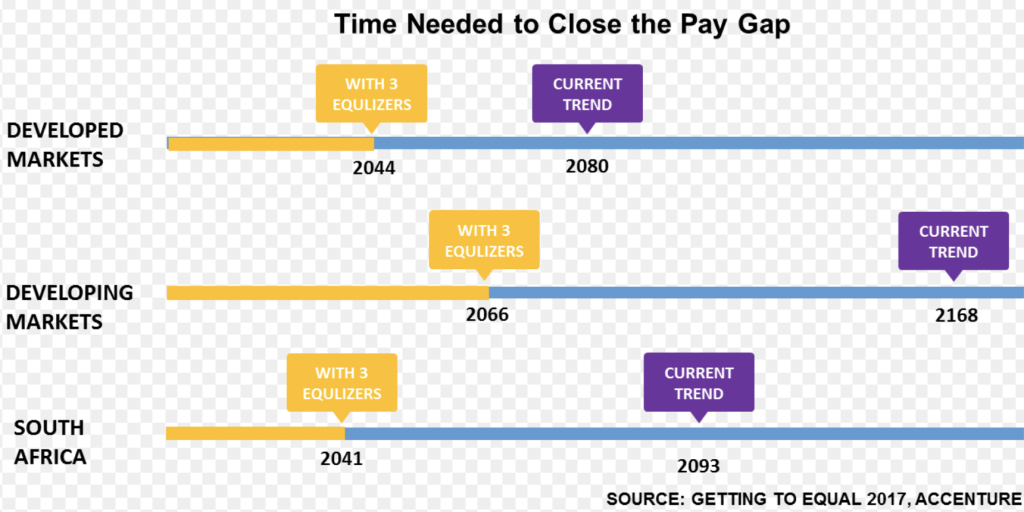

What makes our action more urgent is that unpaid work is just one part of the problem. The other part of the problem is that even in paid work, women are paid way below men, even for the same amount of work. A study by Accenture suggests that if we do certain things, we could close the paid work pay gap by 2041, but if we do too little, it could take up to 2093 to achieve equality. See Figure 3.

With prevailing unemployment and uneven economic participation, women are not suddenly going to be able to buy their way out of unpaid work. Some men may also not afford to buy their loved ones out of it. The solutions are not only monetary.

Slaughtering is not as time consuming as chopping multiple vegetables and meat. Some men, after slaughtering, proceed to cooking the meat though that tends to focus on their favourite parts such as the head, feet and insides. That may be expanded to cooking the stews and grains in order to redistribute the load of cooking equitably.

This text does not succinctly present the problem nor does it propose viable solutions. It is from the small ideas, and unsustainable solutions that the bigger ones would come. If family is the basic unit of society, nothing stops us from starting there to incrementally introduce changes that are directed at making the world better for our daughters and sons. In any case, it is in the family where the unpaid work largely happens.

very helpful, thank you

thank you!

Universitas Telkom

Nice Information, thanks for sharing Greeting : Telkom University

Thanks For Sharing http://dolphin.deliver.ifeng.com/c?b=16033&bg=16027&c=1&cg=1&ci=2&l=16027&la=0&or=1174&si=2&u=https://telkomuniversity.ac.id/

Very interesting article, if u are interested in article like this u can visit my page https://telkomuniversity.ac.id/

Telkom University thanks for information

Эта статья предлагает захватывающий и полезный контент, который привлечет внимание широкого круга читателей. Мы постараемся представить тебе идеи, которые вдохновят вас на изменения в жизни и предоставят практические решения для повседневных вопросов. Читайте и вдохновляйтесь!

Получить дополнительные сведения – https://quick-vyvod-iz-zapoya-1.ru/

После обращения в клинику пациент получает первую подробную консультацию — это может быть очный визит, звонок или заявка через сайт. При необходимости организуется экстренное поступление или выезд нарколога на дом: врач приезжает с полным набором оборудования и медикаментов для оказания неотложной помощи. На первом этапе проводится диагностика: анализы крови, ЭКГ, осмотр профильных специалистов, дополнительное обследование по показаниям. Это позволяет точно определить степень зависимости, выявить осложнения и подобрать эффективную тактику лечения.

Углубиться в тему – https://narkologicheskaya-klinika-balashiha5.ru

Своевременное обращение к специалистам клиники «ВитаРеабилит» — это не только шанс на восстановление здоровья, но и гарантия безопасности пациента и его близких.

Разобраться лучше – http://narkologicheskaya-klinika-podolsk5.ru/platnaya-narkologicheskaya-klinika-v-podolske/

В клинике «АлкоСвобода» используются только проверенные и признанные медицинским сообществом методы:

Узнать больше – медикаментозное кодирование от алкоголизма

Далее назначается инфузионная терапия (капельницы) — специально подобранные растворы и препараты для безопасного выведения токсинов, коррекции водно-солевого баланса, поддержки сердца, нервной системы и печени, нормализации сна и снятия тревожности. Капельница длится от 2 до 4 часов, врач наблюдает за состоянием пациента и, при необходимости, корректирует дозировки, вводит дополнительные средства для купирования судорог, снятия боли, коррекции психоэмоционального состояния.

Выяснить больше – vyvod-iz-zapoya-himki5.ru/

После обращения по телефону или через сайт оператор уточняет детали: симптомы, продолжительность зависимости, адрес и удобное время приезда врача. К выезду всегда готова дежурная бригада — специалисты приезжают к пациенту в Люберцах в течение 1–2 часов, при экстренных состояниях — как можно быстрее.

Изучить вопрос глубже – https://narkologicheskaya-pomoshch-lyubercy5.ru/narkologicheskaya-pomoshch-na-domu-v-lyubercah

Алкоголизм — это не просто вредная привычка или “слабость характера”. Это тяжёлое хроническое заболевание, способное разрушить здоровье, психику, семью, карьеру. На первых порах зависимость подкрадывается незаметно: человек пьёт “по случаю”, для снятия усталости, ради компании. Но постепенно спиртное становится единственным способом отвлечься, расслабиться, уйти от тревог и проблем. Со временем самоконтроль ослабевает, периоды трезвости укорачиваются, а любые попытки “перестать пить” заканчиваются тяжёлым абстинентным синдромом, бессонницей, раздражительностью, головными болями и срывами. В такой ситуации никакие уговоры и угрозы не работают. Необходима профессиональная, комплексная медицинская помощь — именно такую поддержку с максимальной анонимностью и уважением к пациенту предлагает наркологическая клиника «Новая Точка» в Королёве.

Разобраться лучше – лечение алкоголизма стоимость

В клинике «Решение+» предусмотрены оба основных формата: выезд на дом и лечение в стационаре. Домашний вариант подойдёт тем, чьё состояние относительно стабильно, нет риска тяжёлых осложнений. Врач приезжает с полным комплектом оборудования и медикаментов, проводит капельницу на дому и даёт инструкции по дальнейшему уходу.

Ознакомиться с деталями – наркология вывод из запоя

Old Australian games you forgot about: rediscover schoolyard classics and vintage entertainment at https://australiangames.top/

Have You Been Paying Attention won Logie Awards recognising success balancing news information with comedy entertainment through quick-witted topical panel competition. https://australiangameshows.top/

Gaming etiquette in Australia: community standards and respectful play at https://australiangames.top/

Экономьте на строительстве: разберём стоимость монолитной плиты и преимущества каждого варианта https://gratiavitae.ru/

Metabolic Freedom empowers you to take control of your health through simple, science-backed steps. https://metabolicfreedom.top/ metabolic freedom epub

https://comprarcarnetdeconducira.com

https://rijbewijskopenc.com

http://kupprawojazdyb.com

нужна люстра сделать деревянную люстру

мужской костюм на свадьбу мужской костюм интернет магазин

Играешь в казино? ап икс сайт Слоты, рулетка, покер и live-дилеры, простой интерфейс, стабильная работа сайта и возможность играть онлайн без сложных настроек.

детская дизайн интерьера дизайн проект интерьера

Охраны труда для бизнеса охрана труда аудит системы безопасности, обучение персонала, разработка локальных актов и внедрение стандартов. Помогаем минимизировать риски и избежать штрафов.

Проблемы с зубами? альбадент профилактика, лечение, протезирование и эстетическая стоматология. Забота о здоровье зубов с применением передовых методик.

A reliable construction company Costa Blanca — from site selection to delivery of the finished home. Experience, modern materials, and quality control. We manage every detail of turnkey construction, from initial architectural drawings to final interior finishes.

Охраны труда для бизнеса охрана труда аудит системы безопасности, обучение персонала, разработка локальных актов и внедрение стандартов. Помогаем минимизировать риски и избежать штрафов.

Professional сonstruction Moraira: architecture, engineering systems, and finishing. We work with local regulations and regional specifics in mind. We handle permitting and material procurement so you can enjoy the creative process without the stress of management.

Нужен фулфилмент? фулфилмент для маркетплейсов — хранение, сборка заказов, возвраты и учет остатков. Работаем по стандартам площадок и соблюдаем сроки поставок.

Оформления медицинских справок https://med-official2.info справки для трудоустройства, водительские, в бассейн и учебные заведения. Купить справку онлайн быстро

Медицинская справка https://086y-spr.info 086у в Москве по доступной цене — официальное оформление для поступления в вуз или колледж.

Запчасти для сельхозтехники https://selkhozdom.ru и спецтехники МТЗ, МАЗ, Амкодор — оригинальные и аналоговые детали в наличии. Двигатели, трансмиссия, гидравлика, ходовая часть с быстрой доставкой и гарантией качества.

Медицинские справки https://norma-spravok2.info по доступной цене — официальное оформление. Быстрая запись, прозрачная стоимость и выдача документа установленного образца.

Оформление медицинских https://spr-goroda2.info справок в Москве недорого консультации специалистов и выдача официальных документов. Соблюдение стандартов и минимальные сроки получения.

Медицинские справки https://medit-norma1.info в Москве с прозрачной ценой — анализы и выдача официального документа без лишних ожиданий. Удобная запись, прозрачные цены и быстрое получение документа установленного образца.

Медицинская справка https://sp-dom1.ru с доставкой — официальное оформление. Удобная запись, прозрачные цены и получение документа курьером.

Получение медицинской https://gira-spravki2.ru справки с доставкой после официального оформления. Комфортная запись, минимальные сроки и законная выдача документа.

Справка 29н https://forma-029.ru в Москве с доставкой — без прохождение обязательного медосмотра в клинике. Отправка готового документа по указанному адресу.

Медицинские справки https://meduno.info и анализы в Москве — официально и удобно. Сеть из 10 клиник, оперативный прием специалистов и оформление документов по действующим стандартам.

Купить квартиру недорого https://spb-novostroyki-gid.ru актуальные предложения на первичном и вторичном рынке. Подбор вариантов по бюджету, помощь в ипотеке и полное юридическое сопровождение сделки.

Орби казино https://orby-casino.com онлайн-платформа с широким выбором слотов, настольных игр и бонусных предложений. Узнайте об акциях, турнирах и возможностях для комфортного игрового досуга.

Чудові казіно з бонусами — депозитні бонуси, бездепозитні бонуси та Турнір з призами. Обзори пропозицій і правила участі.

Найпопулярніша платформа найкращі онлайн казино – популярні слоти, бонуси та турніри з призами. Огляди гри та правила участі в акціях.

Грайте в онлайн слоти — популярні ігрові автомати, джекпоти та спеціальні пропозиції. Огляди гри та можливості для комфортного харчування.

Найкращі ігри казино – безліч ігрових автоматів, правил, бонусів покерів і. Огляди, новинки спеціальні

Un’accogliente pasticceria https://www.pasticceriabonati.it con fragranti prodotti da forno, classici dolci italiani e torte natalizie personalizzate. Ingredienti naturali e attenzione a ogni dettaglio.

Металлический кованый факел купить с доставкой — прочная конструкция, эстетичный внешний вид и устойчивость к погодным условиям.

Хочешь восстановить мрамор? https://conceptstone.ru устранение трещин, пятен и потертостей. Современные технологии шлифовки и кристаллизации для идеального результата.

Carbon credits https://offset8capital.com and natural capital – climate projects, ESG analytics and transparent emission compensation mechanisms with long-term impact.

Бассейн под ключ цена https://atlapool.ru

Полная статья здесь: https://paradstars.com/catalog/219/

Нужны казино бонусы? https://kazinopromokod.ru — бонусы за регистрацию и пополнение счета. Обзоры предложений и подробные правила использования кодов.

Онлайн покер сайт покерок — турниры с крупными гарантиями, кеш-игры и специальные предложения для игроков. Обзоры форматов и условий участия.

реферат нейросеть реферат нейросеть .

генерация генерация .

ии для учебы студентов nejroset-dlya-ucheby-7.ru .

нейросеть онлайн для учебы nejroset-dlya-ucheby-6.ru .

реферат через нейросеть реферат через нейросеть .

нейросеть текст для учебы нейросеть текст для учебы .

перепланировка в москве pereplanirovka-kvartir9.ru .

ии для учебы студентов ии для учебы студентов .

Все о фундаменте https://rus-fundament.ru виды оснований, расчет нагрузки, выбор материалов и этапы строительства. Практичные советы по заливке ленточного, плитного и свайного фундамента.

Портал о жизни в ЖК https://pioneer-volgograd.ru инфраструктура, паркинг, детские площадки, охрана и сервисы. Информация для будущих и действующих жителей.

реферат нейросеть реферат нейросеть .

нейросеть реферат онлайн нейросеть реферат онлайн .

Все о ремонте квартир https://belstroyteh.ru и отделке помещений — практические инструкции, обзоры материалов и современные решения для интерьера.

Зарубежная недвижимость https://realtyz.ru актуальные предложения в Европе, Азии и на побережье. Информация о ценах, налогах, ВНЖ и инвестиционных возможностях.

ии для учебы студентов nejroset-dlya-ucheby-5.ru .

помощь в согласовании перепланировки квартиры помощь в согласовании перепланировки квартиры .

генерация генерация .

Всё про строительство https://hotimsvoydom.ru и ремонт — проекты домов, фундаменты, кровля, инженерные системы и отделка. Практичные советы, инструкции и современные технологии.

нейросеть для рефератов нейросеть для рефератов .

нейросеть онлайн для учебы nejroset-dlya-ucheby-6.ru .

сайт для рефератов сайт для рефератов .

чат нейросеть для учебы чат нейросеть для учебы .

согласование перепланировки квартиры в москве согласование перепланировки квартиры в москве .

нейросеть реферат онлайн nejroset-dlya-ucheby-5.ru .

реферат через нейросеть реферат через нейросеть .

реферат через нейросеть реферат через нейросеть .

Найкращі бонуси казино — депозитні акції, бездепозитні пропозиції та турніри із призами. Огляди та порівняння умов участі.

Грати в найкраще казіно онлайн — широкий вибір автоматів та настільних ігор, вітальні бонуси та спеціальні пропозиції. Дізнайтеся про умови участі та актуальні акції.

ии для учебы студентов nejroset-dlya-ucheby-7.ru .

сделать реферат сделать реферат .

перепланировка квартир перепланировка квартир .

сделать реферат nejroset-dlya-ucheby-5.ru .

нейросеть пишет реферат нейросеть пишет реферат .

нейросеть для учебы онлайн nejroset-dlya-ucheby-7.ru .

сделать реферат сделать реферат .

нейросеть текст для учебы нейросеть текст для учебы .

перепланировка услуги перепланировка услуги .

нейросеть текст для учебы nejroset-dlya-ucheby-7.ru .

нейросети для студентов нейросети для студентов .

узаконивание перепланировки квартиры pereplanirovka-kvartir9.ru .

проект перепланировки москва проект перепланировки москва .

перепланировка квартиры цена перепланировка квартиры цена .

сделать реферат nejroset-dlya-ucheby-5.ru .

внедрение 1с москва внедрение 1с москва .

сайт для рефератов сайт для рефератов .

Грати в ігри слоти – великий каталог автоматів, бонуси за реєстрацію та регулярні турніри. Інформація про умови та можливості для гравців.

нейросеть текст для учебы nejroset-dlya-ucheby-3.ru .

Онлайн онлайн ігри казино – великий вибір автоматів, рулетки та покеру з бонусами та акціями. Огляди, новинки та спеціальні пропозиції.

стоимость согласования перепланировки стоимость согласования перепланировки .

melbet – sports betting melbet – sports betting .

заказать проект перепланировки квартиры в москве proekt-pereplanirovki-kvartiry22.ru .

melbet скачать официальный сайт melbet скачать официальный сайт .

внедрение 1с производство 1s-vnedrenie.ru .

чат нейросеть для учебы nejroset-dlya-ucheby-8.ru .

чат нейросеть для учебы nejroset-dlya-ucheby-5.ru .

чат нейросеть для учебы nejroset-dlya-ucheby-6.ru .

нейросети для студентов нейросети для студентов .

узаконить перепланировку квартиры стоимость skolko-stoit-uzakonit-pereplanirovku-8.ru .

мелбет скачать официальный сайт мелбет скачать официальный сайт .

melbet betting app melbet betting app .

сделать проект перепланировки квартиры в москве proekt-pereplanirovki-kvartiry22.ru .

внедрение 1с услуги 1s-vnedrenie.ru .

генерация nejroset-dlya-ucheby-6.ru .

нейросеть реферат нейросеть реферат .

сколько стоит перепланировка квартиры в москве skolko-stoit-uzakonit-pereplanirovku-8.ru .

how to download melbet app http://melbetmobi.ru .

проектная организация для перепланировки квартиры proekt-pereplanirovki-kvartiry22.ru .

официальный сайт мелбет официальный сайт мелбет .

внедрение 1с стоимость внедрение 1с стоимость .

melbet скачать на андроид melbet скачать на андроид .

сколько стоит согласовать перепланировку skolko-stoit-uzakonit-pereplanirovku-8.ru .

мелбет старая версия мелбет старая версия .

проект перепланировки и переустройства квартиры проект перепланировки и переустройства квартиры .

официальная версия мелбет http://www.melbet-ru.it.com/ .

внедрение 1c внедрение 1c .

скачать мелбет на айфон скачать мелбет на айфон .

мобильная версия мелбет мобильная версия мелбет .

согласование перепланировки цена согласование перепланировки цена .

заказать проект перепланировки квартиры proekt-pereplanirovki-kvartiry22.ru .

букмекер мелбет букмекер мелбет .

услуга внедрение 1с 1s-vnedrenie.ru .

мелбет на андроид мелбет на андроид .

Онлайн покер Покер онлайн покерок — регулярные турниры, кеш-игры и специальные предложения для игроков. Обзоры возможностей платформы и условий участия.

melbet update version http://melbetmobi.ru/ .

melbet – sports betting melbet – sports betting .

приложение мелбет на андроид приложение мелбет на андроид .

Игровой автомат https://chickenroadgames.top — современный слот с интересной концепцией и бонусами. Подробности о механике и особенностях геймплея.

мелбет казино скачать на андроид мелбет казино скачать на андроид .

мелбет скачать мелбет скачать .

промокод на мелбет промокод на мелбет .

мелбет слоты мелбет слоты .

?n yaxs? Kazino oyununda Minecraft mas?n? canl? dizayn? v? ?lav? xususiyy?tl?ri olan qeyri-adi bir slot mas?n?d?r. Oyuncular ucun xususiyy?tl?r? v? s?rtl?r? n?z?r sal?n.

slot https://minedrop.me/tr/ oyunu, modern grafiklere ve ozgun bir konsepte sahip. Oyunun format?, bahis secenekleri ve oynan?s ozellikleri hakkinda daha fazla bilgi edinin.

мелбет фрибет без депозита мелбет фрибет без депозита .

melbet ru melbet ru .

Попробуйте https://zeusvshades250.com/ru/ — игровой автомат с мифологическим сюжетом, бонусными раундами и оригинальной механикой.

мелбет скачать приложение на андроид мелбет скачать приложение на андроид .

A catalog of cars https://auto.ae/catalog/ across all brands and generations—specs, engines, trim levels, and real market prices. Compare models and choose the best option.

мелбет зеркало скачать мелбет зеркало скачать .

Un sito web https://www.sopicks.it per trovare abbigliamento, accessori e prodotti alla moda con un motore di ricerca intelligente. Trova articoli per foto, marca, stile o tendenza, confronta le offerte dei negozi e crea look personalizzati in modo rapido e semplice.

Dzisiejsze mecze https://mecze-dzis.pl aktualny harmonogram z dokladnymi godzinami rozpoczecia. Dowiedz sie, jakie mecze pilki noznej, hokeja i koszykowki odbeda sie dzisiaj, i sledz turnieje, ligi i druzyny w jednym wygodnym kalendarzu.

Wiadomosci tenisowe https://teniswiadomosci.pl/ z Polski i ze swiata: najnowsze wyniki meczow, rankingi zawodniczek, analizy turniejow i wywiady z zawodniczkami. Sledz wydarzenia ATP i WTA, dowiedz sie o zwyciestwach, niespodziankach i najwazniejszych meczach sezonu.

анализ креативов анализ креативов .

Siatkowka w Polsce siatkowkanews.pl najnowsze wiadomosci, wyniki meczow, terminarze i transfery druzyn. Sledz PlusLige, wystepy reprezentacji narodowych i najwazniejsze wydarzenia sezonu w jednej wygodnej sekcji sportowej.

Koszykowka https://www.koszykowkanews.pl najnowsze wiadomosci, PLK, transfery i wyniki meczow. Sledz polska lige, turnieje miedzynarodowe i postepy zawodnikow, dowiedz sie o transferach, statystykach i najwazniejszych wydarzeniach sezonu.

рекламный креатив рекламный креатив .

бурение скважин обратной промывкой vodoponizhenie-msk.ru .

Jan Blachowicz janblachowicz.pl to polski zawodnik MMA i byly mistrz UFC w wadze polciezkiej. Pelna biografia, historia kariery, statystyki zwyciestw i porazek, najlepsze walki i aktualne wyniki.

водопонизительная скважина vodoponizhenie-moskva.ru .

понижение уровня грунтовых вод иглофильтрами xn—77-eddkgagrc5cdhbap.xn--p1ai .

рейтинг онлайн-школ рейтинг онлайн-школ .

сервис анализа креативов сервис анализа креативов .

скважинное водопонижение vse-o-vodoponizhenii.ru .

система водопонижения иглофильтрами vodoponizhenie-msk.ru .

улучшение баннеров реклама reklamnyj-kreativ8.ru .

бурение скважин обратной промывкой vodoponizhenie-iglofiltrami-moskva.ru .

система водопонижения xn—77-eddkgagrc5cdhbap.xn--p1ai .

проверенные образовательные платформы проверенные образовательные платформы .

позиция карточки в выдаче позиция карточки в выдаче .

вакуумное водопонижение иглофильтрами вакуумное водопонижение иглофильтрами .

бурение скважин для водопонижения бурение скважин для водопонижения .

грунтовое водопонижение грунтовое водопонижение .

upster pro upster pro .

водопонижение котлована иглофильтрами vodoponizhenie-iglofiltrami-moskva.ru .

школа онлайн для детей школа онлайн для детей .

система водопонижения xn—77-eddkgagrc5cdhbap.xn--p1ai .

анализ креативов анализ креативов .

IDMAN TV https://www.idman-tv.com.az live stream online: watch the channel in high quality, check today’s program guide, and find the latest TV schedule. Conveniently watch sporting events and your favorite shows live.

Free online games https://oyun-oyna.com.az with no installation required—play instantly in your browser. A wide selection of genres: arcade, racing, strategy, puzzle, and multiplayer games are available in one click.

Everything about FC Qarabag https://qarabag.com.az/ in one place: match results and schedule, Premier League standings, squads and player stats, transfers, live streams, and home ticket sales.

водопонижение скважинами водопонижение скважинами .

иглофильтровое водопонижение иглофильтровое водопонижение .

Watch Selcuksport TV https://selcuksports.com.az/ live online in high quality. Check the broadcast schedule, follow sporting events, and watch matches live on a convenient platform.

скважинное водопонижение vodoponizhenie-msk.ru .

советы выбора школы best-schools-online.ru .

Exclusivo de Candy Love candylove.es contenido original, publicaciones vibrantes. Suscribete para ser el primero en enterarte de las nuevas publicaciones y acceder a actualizaciones privadas.

анализ наружной рекламы анализ наружной рекламы .

Crystal Lust https://crystal-lust.online is the official website, featuring original publications, premium content, and special updates for subscribers. Stay up-to-date with new posts and gain access to exclusive content.

Brooke Tilli brooke tillii official website features unique, intimate content, exclusive publications, and revealing updates. Access original content and the latest news on the official platform.

Shilpa Sethi http://www.shilpasethi.in exclusive content, breaking news, and regular updates. Get access to new publications and stay up-to-date on the most interesting events.

MiniTinah https://minitinah.es comparte contenido exclusivo y las ultimas noticias. Siguenos en Instagram y Twitter para enterarte antes que nadie de nuestras nuevas publicaciones y recibir actualizaciones emocionantes a diario.

понижение уровня грунтовых вод vodoponizhenie-iglofiltrami-moskva.ru .

улучшение hero карточки улучшение hero карточки .

строительное водопонижение строительное водопонижение .

Eva Elfie https://evaelfie.ing shares unique intimate content and new publications. Her official page features original materials, updates, and exclusive offers for subscribers.

Lily Phillips https://lily-phillips.com offers unique intimate content, exclusive publications, and revealing updates for subscribers. Stay up-to-date with new content, access to original photos, and special announcements on her official page.

Unique content from Angela White angelawhite ing new publications, exclusive materials, and personalized updates. Stay up-to-date with new posts and access exclusive content.

Sweetie Fox https://sweetiefox.ing offers exclusive content, original publications, and regular updates. Get access to new materials, private photos, and special announcements on the official page.

осушение котлованов осушение котлованов .

Souzan Halabi https://souzanhalabi.online shares exclusive content and new publications. Get access to private updates and original materials on the official platform.

иглофильтровое водопонижение иглофильтровое водопонижение .

1вин сайт 1вин сайт

цифровое обучение best-schools-online.ru .

проект на водопонижение vodoponizhenie-msk.ru .

melbet лучшие слоты https://melbet09342.help

Riley Reid https://www.rileyreid.ing is a space for exclusive content, featuring candid original material and regular updates. Get access to new publications and stay up-to-date on the hottest announcements.

Shilpa Sethi shilpasethi official page features unique, intimate content and premium publications. Private updates, fresh photos, and personal announcements are available to subscribers.

Brianna Beach’s exclusive https://briannabeach.online/ page features personal content, fresh posts, and the chance to stay up-to-date on new photos and videos.

Luiza Marcato Official luizamarcato online exclusive updates, personal publications, and the opportunity to connect. Get access to unique content and official announcements.

структура креатива реклама reklamnyj-kreativ8.ru .

Exclusive Aeries Steele http://www.aeriessteele.online/ intimate content, and original publications all in one place. New materials, special announcements, and regular updates for those who appreciate a premium format.

водопонижение на строительной площадке vodoponizhenie-iglofiltrami-moskva.ru .

ии анализ рекламы ии анализ рекламы .

мелбет регистрация по телефону https://melbet09342.help

бурение скважин обратной промывкой бурение скважин обратной промывкой .

Google salaries by position https://salarydatahub.uk comparison of income, base salary, and benefits. Analysis of compensation packages and career paths at the tech company.

Любишь азарт? https://eva-vlg.ru онлайн-платформа с широким выбором слотов, настольных игр и живого казино. Бонусы для новых игроков, акции, турниры и удобные способы пополнения счета доступны круглосуточно.

Bunny Madison https://bunnymadison.online/ features exclusive, intimate content, and special announcements. Join us on social media to receive unique content and participate in exciting events.

melbet вывод элкарт melbet09342.help

водопонижение иглофильтрами грунтовых вод водопонижение иглофильтрами грунтовых вод .

вакуумное водопонижение иглофильтрами vodoponizhenie-msk.ru .

бурение скважин обратной промывкой бурение скважин обратной промывкой .

мелбет лайв казино мелбет лайв казино

1win пополнение Bakai через приложение http://www.1win50742.help

система водопонижения система водопонижения .

1win ставки с телефона https://1win50742.help

откачка грунтовых вод откачка грунтовых вод .

как использовать бонус mostbet как использовать бонус mostbet

Jill Kassidy Exclusives jillkassidy featuring original content, media updates, and special announcements.

Discover Avi Love’s avilove online world: exclusive videos, photos, and premium content on OnlyFans and other platforms.

Scarlett Jones http://www.scarlettjones.in/ shares exclusive content and the latest updates. Follow her on Twitter to stay up-to-date with new publications and participate in exciting media events.

Die Welt von Monalita https://monalita.de bietet exklusive Videos, ausdrucksstarke Fotos und Premium-Inhalte auf OnlyFans und anderen beliebten Plattformen. Abonniere den Kanal, um als Erster neue Inhalte und besondere Updates zu erhalten.

mostbet ставки на теннис Кыргызстан https://mostbet61527.help

Johnny Sins http://www.johnny-sins.com is the official channel for news, media updates, and exclusive content. Be the first to know about new releases and stay up-to-date on current events.

проектирование водопонижения xn—77-eddkgagrc5cdhbap.xn--p1ai .

водопонижение строительных котлованов водопонижение строительных котлованов .

перепланировка москва sostav.ru/blogs/286398/77663 .

Discover the world of LexiLore https://lexilore.ing exclusive videos, original photos, and vibrant content. Regular updates, new publications, and special content for subscribers.

Текущие рекомендации: оснащение ситуационных центров

Serenity Cox http://www.serenitycox.ing shares exclusive content and regular updates. Follow her on Instagram, Twitter, and Telegram to stay up-to-date on creative projects and inspiring events.

Dive into the world of Dolly Little http://www.dollylittle-official.online/ original videos, exclusive photos, and unique content available on OnlyFans and other services. Regular updates and fresh publications for subscribers.

1win приложение не работает https://1win50742.help/

sms activate login sms activate login .

top sms activate services github.com/SMS-Activate-Login .

Купить квартиру https://sbpdomik.ru актуальные предложения на рынке недвижимости. Новостройки и вторичное жильё, удобный поиск по цене, району и площади. Подберите идеальную квартиру для жизни или инвестиций.

sms activator http://www.linkedin.com/pulse/top-5-sms-activate-services-ultimate-guide-virtual-phone-mike-davis-gnhre/ .

smsactivate smsactivate .

проект водопонижения vodoponizhenie-iglofiltrami-moskva.ru .

Discover the world of Comatozze comatozze in exclusive content on OnlyFans and active updates on social media. Subscribe to stay up-to-date on new publications and exciting projects.

The official website of MiniTina minitinah com your virtual friend with exclusive publications, personal updates, and exciting content. Follow the news and stay connected in a cozy online space.

Нужна плитка? старый город плитка большой ассортимент, современные формы и долговечные материалы. Подходит для мощения тротуаров, площадок и придомовых территорий.

бурение скважин для водопонижения бурение скважин для водопонижения .

перепланировка квартир перепланировка квартир .

top sms activate services github.com/SMS-Activate-Login .

водопонижение иглофильтрами водопонижение иглофильтрами .

best sms activate service github.com/SMS-Activate-Service .

best sms activate service http://www.linkedin.com/pulse/top-5-sms-activate-services-ultimate-guide-virtual-phone-mike-davis-gnhre/ .

мостбет промоакции http://mostbet61527.help

грунтовое водопонижение vodoponizhenie-iglofiltrami-moskva.ru .

best sms activation services github.com/SMS-Activate-Alternatives .

мостбет apk установить https://mostbet61527.help

At official spain mirror you can enjoy a very immersive atmosphere with localized themes that resonate well with the Spanish audience. The bonuses are transparent and easy to track within your personal account.

Строишь дом или забор? https://gazobeton-krasnodar.ru продажа газобетона и газоблоков в Краснодаре с доставкой по Краснодарскому краю и СКФО. В наличии автоклавные газобетонные блоки D400, D500, D600, опт и розница, расчет объема, цены от производителя, доставка на объект манипулятором

Нужен газоблок? https://gazobeton-krasnodar.ru/katalog/ каталог газоблоков и газобетона в Краснодаре: размеры, характеристики и цены на газобетонные блоки КСМК. Можно купить газоблоки с доставкой по Краснодару, краю и СКФО. Актуальная цена газоблоков, помощь в подборе, расчет объема и заказ с завода

Нужны ЖБИ? купить плиты перекрытия широкий ассортимент ЖБИ, прочные конструкции и оперативная доставка на объект. Консультации специалистов и индивидуальные условия сотрудничества.

услуги по перепланировке квартир услуги по перепланировке квартир .

Visiting official gaming mirror gives you access to a legitimate gaming platform with clear terms and conditions regarding bonuses. The registration is fast, and the verification process didn’t take more than a few hours in my case.

smsactivate smsactivate .

top sms activate alternatives top sms activate alternatives .

best sms activate service http://www.linkedin.com/pulse/top-5-sms-activate-services-ultimate-guide-virtual-phone-mike-davis-gnhre/ .

Unique content from Gattouz0 Officiall – daily reviews, new materials, and the opportunity for personal interaction. Stay connected and get access to the latest publications.

Discover the world of CandyLove Officiall: exclusive content, daily reviews, and direct communication. Subscribe to receive the latest updates and stay up-to-date with new publications.

Contenido exclusivo de Karely Ruiz: resenas diarias, nuevos materiales y la oportunidad de interactuar personalmente. Mantengase conectado y acceda a las ultimas publicaciones.

Immerse yourself in the world of CrystalLust Officiall: unique content, daily reviews, and direct interaction. Here you’ll find not only content but also live, informal communication.

melbet plinko как играть melbet plinko как играть

Exclusive from SkyBri Officiall – daily reviews, new publications, and direct communication. Subscribe to stay up-to-date and in the know.

sms activate website sms activate website .

sms activate alternatives sms activate alternatives .

мелбет служба поддержки мелбет служба поддержки

согласование перепланировки согласование перепланировки .

official page ElleLee features hot posts, private selfies, and real-life videos. Subscribe to receive daily updates and exclusive content.

The official LexisStar page features daily breaking news, personal selfies, and intriguing content. Subscribe to stay up-to-date with new updates.

The official delux_girl channel features daily hot content, private selfies, and exclusive videos. Intriguing real-life moments and regular updates for those who want to get closer.

Discover the world of NaomiHughes Official: daily vibrant content, candid selfies, and dynamic videos. Real life moments and regular updates for those who appreciate a lively format.

Discover the world of MickLiterOfficial: behind-the-scenes stories, bold provocations, and personal footage. All the most interesting content gathered in one place with regular updates.

sms activate service sms activate service .

sms activator http://www.linkedin.com/pulse/top-5-sms-activate-services-ultimate-guide-virtual-phone-mike-davis-gnhre/ .

intriguing publications ReislinOfficiall and new materials appear regularly, creating a truly immersive experience. Personal moments, striking provocations, and unexpected materials are featured. Stay tuned for new publications.

Descubre el mundo de Lia Lin: historias tras bambalinas, provocaciones audaces y videos personales. Todo el contenido mas interesante reunido en un solo lugar con actualizaciones periodicas.

sms activate login sms activate login .

перепланировка квартиры согласование sostav.ru/blogs/286398/77663 .

smsactivate smsactivate .

smsactivate smsactivate .

The best of MilaSolanaOfficial – sharing all the most interesting content in one channel. Behind-the-scenes atmosphere, provocative mood, and personal snippets. Stay tuned and don’t miss any new releases.

exclusive revelations MonalitaOfficial genuine passion and bold aesthetics. Private content you’ll find only here—directly from the author, without filters or unnecessary boundaries.

passionate atmosphere Amadani Officiall openness and a personal format of communication. Exclusive content, created without intermediaries—only for those who want more.

honest revelations AlinaRai vivid emotions and a sensual atmosphere. Unique private content, available only on this page—directly from me.

sms activate service sms activate service .

best sms activate service github.com/SMS-Activate-Alternatives .

перепланировка помещения sostav.ru/blogs/286398/77663 .

mostbet изменить пароль https://www.mostbet61527.help

1вин mastercard вывод http://1win50742.help/

Vivid revelations SweetiefoxOfficiall sensual aesthetics, and a signature format. Private materials created without boundaries or templates—available only in one place.

Pure emotion ReislinOfficiall bold presentation, and a private format without boundaries. Exclusive content, personally created and available only here—for those who appreciate true energy.

Candid style DianaRider vibrant passion, and a unique atmosphere. Private publications and unique materials that you’ll find exclusively in this space.

Boldness and sincerity LunaOkko maximum intimacy. Personal content without intermediaries—only here and only directly from me.

smsactivate smsactivate .

top sms activate services github.com/SMS-Activate-Alternatives .

Maximum candor Princess lsi vibrant energy, and a private atmosphere. Exclusive content is personally created and available only here—for those ready for a truly unique experience.

A bold image LunaOkko strong charisma, and a personal communication format. Private publications and special materials revealed only to our audience.

Frank emotions RaeLilBlac Officiall captivating aesthetics, and a personalized format. Content without unnecessary filters—directly from the author.

The energy of passion Romi Rain sincerity, and private access. Unique publications created for those who appreciate a personalized and bold format.

Играешь в казино? https://eva-vlg.ru популярная онлайн-платформа с большим выбором слотов, настольных игр и лайв-казино. Бонусы для новых игроков, регулярные акции и удобные способы пополнения доступны круглосуточно.

Bold aesthetics SiriDahl personal revelations, and an intimate atmosphere. Exclusive content is created without compromise—only for our audience, and only here.

Нужен промокод казино? https://promocodenastavki.ru получите бесплатные вращения в популярных слотах. Актуальные бонус-коды, условия активации и пошаговая инструкция по использованию для новых и действующих игроков.

Sensual style CocoLovelock vibrant energy, and an unfiltered format. Unique materials available exclusively in this space.

Лучшее казино онлайн https://detsad47kamyshin.ru слоты, джекпоты, карточные игры и лайв-трансляции. Специальные предложения для новых и постоянных пользователей, акции и турниры каждый день.

best sms activate service github.com/SMS-Activate-Alternatives .

Нужен компрессор? https://macunak.by для производства и мастерских. Надёжные системы сжатого воздуха, гарантия, монтаж и техническая поддержка на всех этапах эксплуатации.

Play unblocked games online without registration or downloading. A large catalog of games across various genres is available right in your browser at any time.

Работаешь с авито? авито для бизнеса профессиональное создание и оформление Авито-магазина, настройка бизнес-аккаунта и комплексное ведение. Поможем увеличить охват, повысить конверсию и масштабировать продажи.

Последние обновления: Экзистенциальная психотерапия: Процедура и Отзывы – Путь к Пониманию Себя

buy hash in prague marijuana

weed in prague buy hemp in prague

buy hemp in prague weed delivery in prague

420 day in prague praha 420

420 movement in prague 420 store in prague

thc gummies shop in prague buy cannafood in prague

cannabis for sale in prague cannabis store in prague

kush for sale in prague thc joint shop in prague

buy thc joint in prague cannabis shop in prague

marijuana marijuana

cannabis for sale in prague buy thc chocolate in prague

praha 420 buy weed in telegram

thc vape for sale in prague hashish delivery in prague

buy cannabis in prague thc weed in prague

buy thc joint in prague cannabis store in prague

cannabis buy weed in prague

buy thc gummies in prague prague 420

hemp for sale in prague cannafood delivery in prague

marijuana delivery in prague cannabis

Jouez-vous au casino? https://sultan-willd-fr.eu.com une plateforme de jeux moderne proposant une variete de machines a sous, de jackpots et de jeux de table. Inscription et acces faciles depuis n’importe quel appareil.

Check online hub for essential information regarding local community initiatives and the strategic goals set by leadership. The layout is very clear, which makes it easy to find specific data about upcoming public events and policy updates without much effort. It really helps bridge the gap by providing transparent and timely information that matters to every active citizen in the region.

At online slots portal you will find an extensive library of licensed slots and live dealer tables that definitely cater to all types of players. The site has a reputation for offering very competitive bonuses with fair wagering requirements, making it a solid choice for both beginners and pros. I’ve personally found their withdrawal process to be quite efficient, which is always a top priority when choosing a new platform.

Visit more info to find unique entertainment tips and detailed guides about the latest lifestyle trends. This platform is well-researched and provides a fresh perspective for anyone interested in high-quality content that isn’t covered by mainstream blogs. I especially like how they categorize their posts, making it easy to navigate through different themes without feeling overwhelmed.

Try https://casamiamarblehead.com/ if you are looking for the official Mr.Jackbet platform with the most reliable slots and betting options. This destination is very professional and provides all the necessary details and service descriptions you might need before you start playing for real. It’s a great example of a secure environment that values transparency and makes it easy for users to find exactly what they need.

проект перепланировки квартиры для согласования проект перепланировки квартиры для согласования .

YouTube caiu caiu.site .

Топ 10 казино онлайн Топ 10 казино онлайн .

Казино Рокс Казино Рокс .

1win verificare email http://1win5805.help/

заказать кухню в интернете заказать кухню в интернете .

купить заказать кухню купить заказать кухню .

Inside top Indian slots you will find a massive selection of games specifically tailored for the Indian market, including hits like Teen Patti and Andar Bahar. The platform utilizes high-level encryption to ensure all transactions and personal data remain secure at all times. I also found that they offer excellent local deposit options, which makes the whole experience much more convenient for users in the region.

On https://boomerang-casino-el.gr.com/ you can enjoy a very engaging loyalty program that rewards active players with frequent cashback and exclusive tournament invitations. The platform is highly stable and performs well on both desktop and mobile browsers, ensuring you never miss a beat. It’s a great choice for those who value long-term rewards and a consistent gaming environment with plenty of variety.

At Amunra bonus players in the Czech region can experience high-quality slots and live dealer games in a completely secure and localized environment. The site supports popular local payment methods and offers 24/7 customer support to resolve any technical or account issues as quickly as possible. It’s a very reliable destination for those looking for a smooth registration process and a diverse library of certified casino games.

Playing Plinko game link is a fantastic way to experience this classic arcade-style game with modern graphics and certified fair mechanics. The interface is very straightforward, allowing you to jump straight into the action without dealing with overly complicated settings or menus. It’s perfect for those who enjoy quick gaming sessions where the outcome is clear and the gameplay remains consistently engaging.

Visit Greek betting portal if you are looking for a premium gaming experience in Greece with a heavy focus on sports-themed slots and live betting. The site is fully localized, making navigation easy for Greek speakers, and the bonus offers are quite generous for new registrations. They have a great mix of classic casino games and modern sportsbook features that keep the overall experience very diverse.

заказать проект перепланировки квартиры teletype.in/@jorik11/proekt-dlya-pereplanirovki .

Discord down caiu.site .

Казино онлайн бесплатно Казино онлайн бесплатно .

Новые онлайн казино 2026 Новые онлайн казино 2026 .

купить заказать кухню купить заказать кухню .

заказать кухню с замером zakazat-kuhnyu-2.ru .

Visiting Spanish tech portal is essential for those tracking the latest digital trends and platform launches in Spain for the upcoming year. The site provides technical details and roadmap updates that are quite valuable for anyone involved in the local tech or gaming sectors. It serves as an official hub for news and announcements regarding several key digital initiatives starting in early 2024.

Reading casino review portal will give you a detailed overview of the platform’s features, from its unique space-themed design to its massive game library. This expert review breaks down the pros and cons, helping you decide if their current welcome package fits your playing style. It’s a very helpful resource for anyone who likes to do a bit of research before committing to a new online casino.

Visiting best player site gives you a detailed look into the career and professional achievements of one of Mexico’s top football stars. The site includes exclusive content, career milestones, and regular updates that are perfect for dedicated fans of the midfielder. It’s a well-organized tribute to his journey from local clubs to the international stage and his ongoing impact on the sport.

On official sports hub you will find a wide range of articles covering everything from local football to international sports tournaments. It’s a comprehensive portal for anyone who wants to stay updated on Mexican sports without having to visit multiple different news sites. The quality of the reporting is very high, and they cover a diverse range of athletic disciplines beyond just soccer.

mostbet промоакции http://www.mostbet52718.help

заказать кухню цены заказать кухню цены .

согласование перепланировки под ключ согласование перепланировки под ключ .

This https://rayados-de-monterrey.com.mx/ portal provides comprehensive coverage of the club’s history, current roster, and community initiatives in the Monterrey region. I check it regularly for official injury reports and transfer news to stay updated on the team’s latest developments. It’s a great resource for dedicated supporters who want to follow every aspect of the club’s journey in the league.

заказать кухню заказать кухню .

Казино сол Казино сол .

See Toluca portal link for the most accurate statistics and official statements directly from the club’s management this season. The site offers a detailed look at the team’s performance metrics and upcoming match analysis, which is perfect for fans who like to dive deep into the numbers. It’s a professional and well-maintained site that serves as the official voice of the team for its loyal fanbase.

The 365bet.com.mx/app is the recommended tool for Mexican players who want instant access to their betting accounts from any location. It’s fast, secure, and includes all the features found on the main website, such as live streaming and instant cash-outs. Downloading the official app ensures you have the most stable connection possible, even when you’re away from your desktop.

Checking Chivas Mexico link is a must for any fan looking for the latest news, match schedules, and official team updates. The portal provides in-depth coverage of the club’s performance and includes exclusive interviews with players and coaching staff throughout the season. It’s the most reliable source for verified information regarding upcoming fixtures and official club announcements.

internet down caiu.site .

Казино Рокс Казино Рокс .

заказать кухню цена zakazat-kuhnyu-3.ru .

pariuri sportive Moldova 1win pariuri sportive Moldova 1win

заказать индивидуальную кухню zakazat-kuhnyu-2.ru .

1win idman tətbiqi http://www.1win5763.help

типография в Москве https://scrapbox.io/toppost/Как_отличить_типографию_полного_цикла_от_посредника%3F .

сделать проект перепланировки квартиры в москве teletype.in/@jorik11/proekt-dlya-pereplanirovki .

секс порно шлюха порно с озвучкой

жирные шлюхи шлюхи даю

Рейтинг лучших онлайн казино Рейтинг лучших онлайн казино .

заказать кухню в спб от производителя kuhni-spb-41.ru .

согласование перепланировки москва согласование перепланировки москва .

грузчик экспедитор услуги грузчиков расценки

грузчики недорого грузчики

заказать кухню заказать кухню .

Казино онлайн играть Казино онлайн играть .

1win descarcare aplicatie casino 1win descarcare aplicatie casino

купить заказать кухню купить заказать кухню .

Play online bloxd-io for free right in your browser. Build, compete, and explore the world in dynamic multiplayer mode with no downloads or installations required.

Football online https://qol.com.az goals, live match results, top scorers table, and detailed statistics. Follow the news and never miss the action.

pin-up казино играть https://games-pinup.ru

El sitio web oficial de Kareli Ruiz http://www.karelyruiz.es ofrece contenido exclusivo, noticias de ultima hora y actualizaciones periodicas. Mantengase al dia con las nuevas publicaciones y anuncios.

Lily Phillips https://lilyphillips.es te invita a un mundo de creatividad, conexion y emocionantes descubrimientos. Siguela en Instagram y Twitter para estar al tanto de nuevas publicaciones y proyectos inspiradores.

заказать кухню онлайн заказать кухню онлайн .

заказать кухню под ключ zakazat-kuhnyu-2.ru .

1win actualizare aplicatie http://1win5805.help/

услуги печати в Москве https://webyourself.eu/blogs/1805413/%D0%9E%D0%B1%D0%B7%D0%BE%D1%80-%D1%80%D1%8B%D0%BD%D0%BA%D0%B0-%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%B8%D0%B3%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%84%D0%B8%D1%87%D0%B5%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D1%85-%D1%83%D1%81%D0%BB%D1%83%D0%B3-%D0%9C%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B2%D1%8B-%D1%82%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B4%D1%8B-%D0%B8-%D1%86%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%8B .

проектная организация для перепланировки квартиры teletype.in/@jorik11/proekt-dlya-pereplanirovki .

Лучшие онлайн казино Лучшие онлайн казино .

Vivo caiu Vivo caiu .

Казино лучшее онлайн Казино лучшее онлайн .

кухня глория kuhni-spb-41.ru .

помощь в согласовании перепланировки квартиры помощь в согласовании перепланировки квартиры .